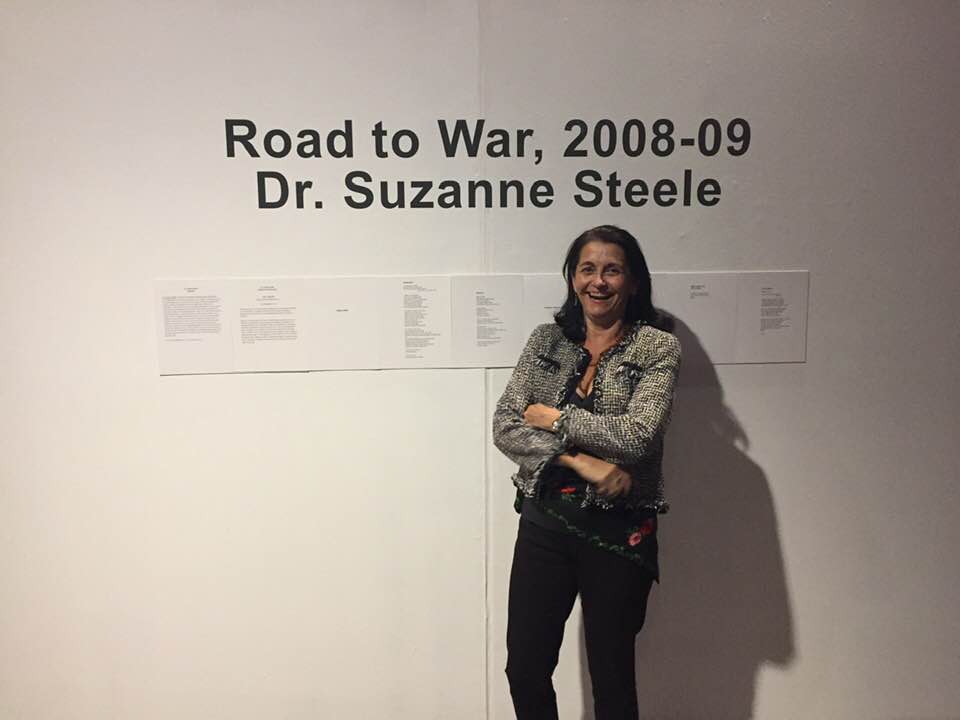

24 hrs leave

war, this word so small so worried

over and out; you and I, self-storied,

the click of lips, our hips tented

into one, a shelter, new conquered

land; small, there it is again, 24 rented

hours just for this; wars’ dragonflies

lapus lazuli, gossy-gold, the fuse; my

heat, the sheets, the folds, and you.

©S.M. Steele 2009

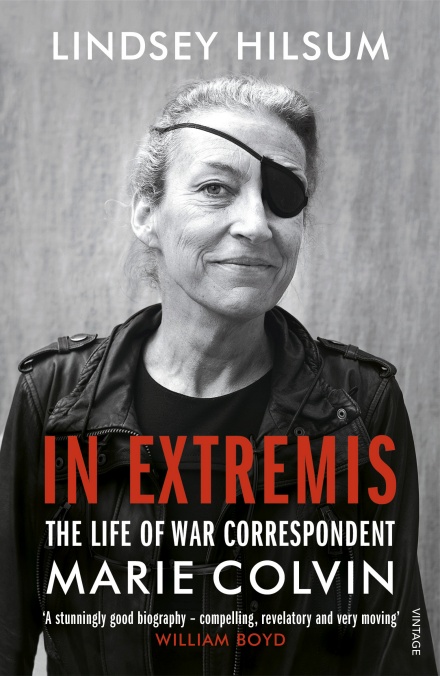

For me some books are better read in summer than winter. This is the case with, In Extremis: The Life of War Correspondent Marie Colvin (2018), a biography of Colvin by war correspondent Lindsey Hilsum. I am reading it in the full light of July. I bought the book last winter when it first came out but could not bear to read it. Given my work of almost a decade ago, far different than Colvin’s, and my exposure to the trauma of war, far less, I find this compelling biography to be at once fascinating and depressing. Ultimately it details the price one woman paid for illuminating the human condition in war, a price her family and friends and colleagues must continue to pay.

In 2012, I had the good fortune to meet David Loyn at the Frontline Club in London, a club founded by, and for, frontline journalists. I was introduced to Loyn by a retired British Brigadier-General who had contacted me for an interview for his own Master degree on war poetry. The retired general, a 40-something year old and veteran of Iraq, was then working with the media and was a member of the club, and as I’d mentored the general with his own work, he was eager to oblige with some quid pro quo.

At the time, I wanted to speak with Loyn for my PhD, a study of war narratives and the inherent challenges of finding an appropriate artistic form, and the process the artist undergoes in war. Finally, I attempted to explore the rather old-fashioned notion of truth in war. As a Canadian War Artist (2008-10 Task-Force 3-09 A’stan with 1PPCLI), I was interested in hearing the front-line journalist point of view, how they tackle story – I felt this would add a dimension to my dissertation that would contextualize my central arguments. Central to my research, I wanted to know how war tackles frontline journalists. Near the end of our interview, Loyn suggested he introduce me to his very good friend and comrade, Marie Colvin. He told me that she was due back to London within a few weeks and he’d facilitate this. I remembered this striking woman with the eyepatch and was very interested in meeting her. But within 10 days or so, she was dead, targeted in Homs, Syria. I sent Loyn a letter of condolence.

My experience of journalists, or at least how they are often perceived by soldiers in theatre or on military exercises, is one of caution. During my tenure as a war artist (a poet for heaven’s sake), soldiers avoided me like the plague as they thought I was a journalist, due to my constantly taking notes and photographs. After their officers explained who I was, why I was there, and how to behave around me (as normal as possible), they slowly relaxed. The Commanding Officer of the battalion I accompanied on the road to war advised that I ‘be ever-present, become like the furniture and the boys will soon forget you’re there’.

I spent thousands of hours with the boys (and I include women in this term), mostly recruits rather than officers. I slept on the ground alongside them, rattled in Light Armour Vehicles (LAVs) for hours on end, suffered the dreaded GI (gastro-intestinial virus) with them and got hauled off live-fire and then quarantined and forgotten, helped feed them by getting up with the cooks at 4 a.m., and visited them on the frontlines. Interestingly, I got more street-cred with them for suffering the GI and being forgotten, than I did flying outside the wire to them! (‘You’re one of us now Ma’am’ they told me). I became part of the furniture. Almost. But one thing I never tried to be, was one of them. Nor did I ever speak for them. And contrary to what the poem above suggests, I did not fraternize. (I think I was a mom-figure to them, actually.)

I liken war to a very hot frying pan of sizzling oil. As anyone who cooks will know, ingredients thrown into the hot, hot pan will either fry to a blackened, inedible crisp, or, the heat can bring out the very best of flavours, the sharpest. It’s all in the care and timing. In war, one sees the very best of human behaviours, and the very worst (on the homefront too, I should add). And war can be gaudy or addictive, as I write in my poem, a poem imagining a 24 hour leave:

wars’ dragonflies

lapus lazuli, gossy-gold, the fuse …

Over the long haul, if one throws in the MSG of PTSD, a slow slither of a flavouring comes forth, one that quickly turns war from intriguing to craving, to addiction. This is the recipe that I refer to in my dissertation as being ‘the sensual and moral conversion’ (Lande qted in Steele, 25-27), of the war artist, or, in the case of Colvin, the war correspondent. This notion of becoming someone else, through physical and moral conversion, was developed from my reading of sociologist Brian Lande’s fascinating study ‘Breathing Like a Soldier: culture incarnate’ (2007) in which Lande signed up for basic training so he could understand the process of becoming a soldier. That the conversion happens in the highly-pressurized physical environment of the war zone, or what I refer to as ‘The Forbidden Zone’ (with reference to Mary Borden’s 1928 narrative), fixes the conversion. I believe these ideas hold true for war journalists too.

And I think this is why I find Colvin’s story by Hilsum so daunting to read, especially in winter – it is a cautionary tale as much as a well-researched and well-written biography. One reads of Colvin’s choices, her braveries, and sometimes her foolhardiness, and then of her private life and choices therein, many of them disastrous. Colvin is portrayed as a wonderful friend, a great companion, and a generous colleague – someone I’d have loved to meet – an attractive spirit who loved sailing (something I’ve learned too, these past years) and a good party. But Hilsum’s brilliant interspersing of Colvin’s diary entries and excerpts from Colvin’s dispatches are often just too painful to read – the ones from the Serbian war I had to skip – I know too much about vicarious trauma to know what we put in we cannot take out, I’ve met too many veterans of that war and have learned of their pain.

What is most painful in Hilsum’s biography of her colleague and friend, is that we know the outcome, the divorces, the estrangements, the deaths, and ultimately, Colvin’s death. At times while reading this, all I want to do is shout out to Colvin “No!!! Don’t do it!” – whether this be a marriage or another trip to the war zones. And this is the brilliance of the book, Hilsum carefully lays out the sensual and moral conversion of the young girl, Marie, born to a big, happy, Irish-American Catholic family, to the war-weary Colvin. And as the very best of biographers, Hilsum gets out of the way of the story. This is no mean feat given Hilsum’s own illustrious career as a journalist working on the frontlines of some of the world’s most difficult conflicts. Further, as Hilsum states in a Press Gazette article, she did not want to appear to be “buying into or helping create the myth of Marie and the glamour of the war correspondents”. But Hilsum pulls it off. She has written a great biography of one of my generation’s most committed and skilful journalists – not a Martha Gelhorn (Colvin’s hero) for our age, but a Marie Colvin, an original.

My condolences to Marie Colvin’s family, colleagues, and friends.